I didn’t come to the decision to perform burlesque in a wheelchair easily. I didn’t even own a personal wheelchair when I began reentering the burlesque world, in fact. At that point, I had been struggling with ever-increasing pain for years, gradually beginning to accept that every time I tried to get onto my bike, climb a flight of stairs, walk around town, or move to a rhythm, I was hurting myself in potentially irreparable ways.

Despite not having performed on a stage in years and not knowing how I was going to create an act when I had been advised by doctors that dancing would degrade my constantly unstable joints, I joined the Black Cherry Mentorship Program in Tucson called “Burlesque for the Soul.” I began dreaming up a chair act with the guidance of my mentors, since it was much more difficult for me to injure myself when I was seated, and it seemed like a natural foundation for a burlesque act. At that point the subject of mobility aids to increase the freedom in my personal life had been broached, but I rejected the idea – wheelchairs and leg braces and canes all meant something to me that I couldn’t stomach.

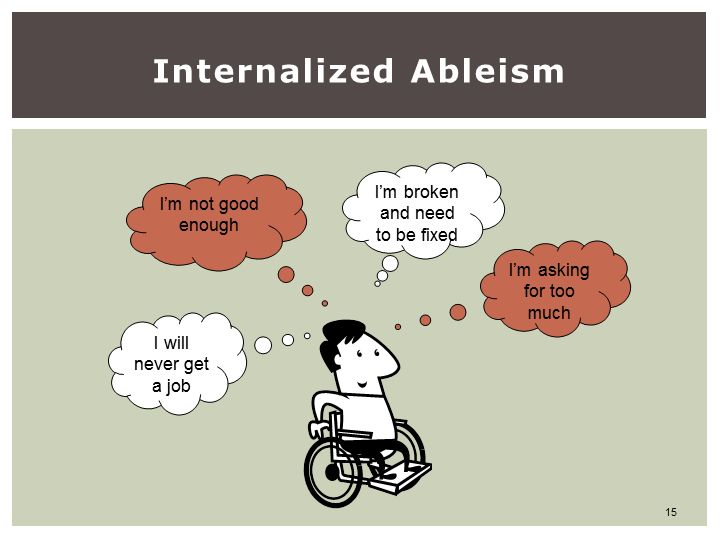

So, when Inga Kaboom, the leader of our little tribe, looked me in the eyes and asked me why the chair that I would eventually celebrate with on stage couldn’t be a wheelchair, I recoiled. Yes, I couldn’t walk more than a couple feet without something subluxing, the pain in my joints blinded and sickened me if I tried dancing on my legs, and I was in doctors’ offices several times a week, but I wasn’t a “wheelchair person.” Whatever that meant, it couldn’t be me.

I wasn’t “disabled.”

—

What do you think of when you hear the word “disability”?

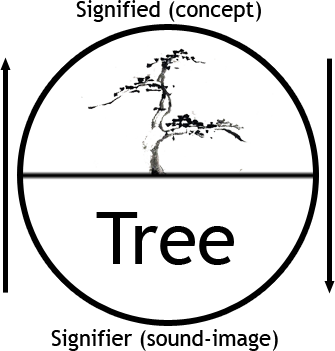

There are many potential answers to this question, but it usually is accompanied by a mental image, a “disabled person” that we conjure in our minds that reflects the experiences that we’ve had, the media that we’ve consumed, the people that we’ve met, and the stories that we’ve heard. It’s part of the way that our minds work with language that visual representations accompany the words that we read or hear, translating signifiers into signifieds (I knew Saussure would come in handy some day).

I’m not going to say that the image you chose when asked to think about the word “disability” was “wrong” – I don’t know you, your mind, or your experiences, and one of the first lessons that I learned as an advocate for myself and for others was to avoid assuming whenever possible. It’s also not a great plan to shame people for their impulse to turn the signifier of “disability” into the image that their experiences have coded into their minds. Stopping the train of signification is extremely difficult, no matter what my English department may have said, and it’s not a battle that I find worth fighting.

However, as a disabled woman, advocate, and burlesque performer, I’ve repeatedly experienced the damage that those preconceived perceptions of disability can create, both internally and externally. My ableist preconceptions about disability and wheelchair-use prevented me from seeing an invaluable tool as an option for my life or for my performance. I had an image in my head, a signified, that equated wheelchairs and disability with “giving in,” with admitting that I was “broken,” and with a future that was fixed in struggle and pain. This is because my image was limited. I was remembering the horribly ableist phrase “confined to a wheelchair” and didn’t consider how freeing it could be to no longer collapse on the street after walking a block, how much farther I could go and how much more I could do with a wheelchair as a tool.

In a way, my image wasn’t entirely incorrect. In order to accept that chair into my life, I had to accept that the world would begin to look at me differently and I had to validate that, yes, my pain was real and it disabled me. It would make what I had considered my invisible, private pain suddenly very visible.

This is the crux of the issue with the images that we conjure into our heads when we think of “disability.” Most likely, your mind selected some visible indication of disability to cling to – a wheelchair, a cane, a physical sign that someone’s insides aren’t shaped the way that we would consider normal. This is the kind of thinking that told me that I wasn’t “disabled” as long as I didn’t use a wheelchair, despite my pain and my doctors and my inability to live the way that I used to. This is also the kind of thinking that results in images like this one and that contribute to the assumption that people in wheelchairs must be suffering from paralysis of some kind, or are otherwise entirely incapable of standing.

The truth is that I was living with a disability long before that moment in Burlesque for the Soul, wheelchair or not. It was just an invisible one.

Despite some general issues with phrasing, the ADA remains a reliable source for the legal definition of disability. “The ADA defines a person with a disability as a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activity. This includes people who have a record of such an impairment, even if they do not currently have a disability. It also includes individuals who do not have a disability but are regarded as having a disability. “ (https://adata.org/faq/what-definition-disability-under-ada) The limits that I had accrued and experienced as a result of my condition certainly met this definition long before a wheelchair came into my life. Yet I was certainly not what would spring to anyone’s mind when they thought about the word “disability.”

An “invisible” disability is one that is “not immediately apparent.” Invisible disabilities vary extremely in severity and affect, just as visible ones do, but they impact lives in myriad ways. They require attention and forethought and management. In my home, as I walk slowly from my bedroom to the living room down the hall, my disability is invisible to an onlooker. Underneath the surface, however, I am engaging in complicated muscle contractions that my physical therapist has taught me to protect my hips, I’m twisting my feet against the floor to force my leg to align correctly, and I’m willing relaxation down through the loud and angry pain by silently repeating the phrases from my guided meditations.

I am a “disabled” woman, and I accept (and celebrate) that now. Sometimes that disability is visible and sometimes it is invisible, but it doesn’t disappear. While I can’t ask you or anyone to stop the process of signification that leads you to equate disability with a visible signifier, I can ask you to stamp that signifier with a caveat: this is just one story of disability. This is just one manifestation along a vast spectrum of ability and disability and there would be no way of knowing if the next person that I see on the street is disabled or not if they did not choose to tell me. If a person in a wheelchair stands to reach something on the top shelf, your reaction shouldn’t be to question her use of the chair as a tool to increase her mobility. It should be to wonder whether there might be a way for the store to make her use of that space easier to navigate.

—

After struggling with my own internalized ableism for weeks, I purchased my first wheelchair. I customized it, painting it and covering it in rhinestones and tufting cushions for it. I did all of this because the first time that I used it, out on the streets, I marveled at the instinct to say that people are “confined” to wheelchairs. I was liberated by my chair – this tool that helped me to go farther and do so much more than I could have without it. When I move with it and around it on stage, my disability shifts between visible and invisible. There are moments where my choreographed muscle movements mask my syndrome enough that it is no longer “apparent” and it might be easy to dismiss any affiliation I might have with that limited signifier “disabled.” My disability is always there, though, visible or not. My use of my chair is not what makes me a woman and a performer with a disability. It is what makes it “apparent” to you, and it is also what makes me capable of performing at all.

—

Jacqueline Boxxis the only Tucson burlesque performer who brings her wheelchair, her canes, and her leg braces on stage and makes them both visible and enticing. Her background before disability involved trapeze, hooping, cabaret, theater, bellydance, swing dance, ballet, and numerous other kinds of performance art, including touring with The Dresden Dolls as part of their Brigade. Her mobility decreased gradually and these performance outlets lessened as well. However, linking up with Tucson’s Black Cherry Burlesque and participating in their Burlesque for the Soul program altered her understanding of what burlesque performance could mean. She now combines her performance art with her background as a PhD student in order to alter conceptions of disability through academic scholarship and workshops on mindful movement in addition to her stage acts.

Jacqueline’s acts are all related in some way to her experience with chronic pain and limited mobility, and she strives to bring attention through glamour and spectacle to disability. Her extended tagline expresses this intention: Miss Disa-burly-TEASE.